The past couple of months have been especially good for me. Plenty of interesting reading and ruminating, yes, but also simmering excitement about some eagerly awaited news, some personal happy tidings and immense familial joys. My cup runneth over. Of course, the world around and beyond isn’t exactly a happy one and some of its continuing wretchedness threatened to shadow my bliss however momentarily. But that’s in the natural course of things, the near mandatory mix of the good, the not so good and the outright bad. Some rain, some sunshine. And as those inclined philosophically would agree, without the one, we wouldn’t really appreciate the other.

Which doesn’t mean that one needs stoically endure the bad. I could be philosophical about my sorrows when I have a more immediately present basket of happiness to bask in. But if the bad were to gnaw away the beneficence of the good, then I wouldn’t rest until I’d set things right, at least those that fall within my ambit, those that I can.

Broadly speaking, the journey of human societies through the centuries has been marked by conscious correction of the bad for the better, for people individually and collectively. Thinkers and doers have striven assiduously to identify social and personal malaises and find remedies or ways to surmount them. Historically, some of the ways have included battles and wars, marches, protests and revolutions. As of today these struggles continue. Of course, what constitutes a betterment remains debateable. The meat-poison conundrum is mostly inescapable.

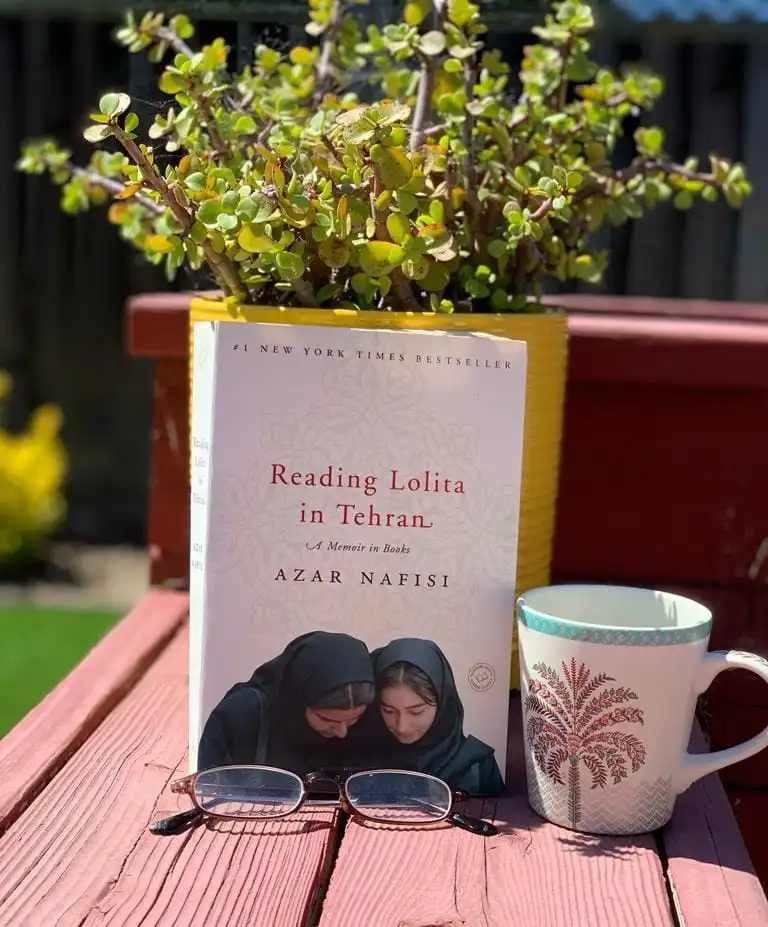

Some of the contentious nature of ‘betterment’ featured prominently in my recent reading: Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran, an exquisitely written memoir about the author’s life in Iran both prior and post the Islamic Revolution, a revolution that not only dismantled the Shah’s monarchy, but also shook the very foundations of the society she lived in. I had read Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi earlier, that through the graphic novel told the story of an adolescent girl coming to understand the fallouts of the revolution. Nafisi’s account brought in many more layers and textures to the understanding of those rapidly changing times, changing perspectives, and changing people. The promise and hope, the disappointment and rancour.

Nafisi taught in the University of Tehran where she steered her class of students through some of the seminal works in literature in English. She deliberately chose texts that she considered subversive, ripping through convention and convenience, challenging settled dogmas, questioning peremptory presumptions of societal positions, and always examining the role of women in them. Vladimir Nabokov and Henry James, Fitzgerald and Austen entered her class, confronting the youth that sat within, compelling them to grapple with the ideas and emotions that swirled in their books, fathom the frailties and strengths of their characters, to recognise them in themselves and people around. Willing a generation post-Revolution to step away from the very regulated Islamic Republic into the completely free Republic of Imagination. Daring them to think more, to dream more, to search for more, to never settle for less.

In tandem with her analysis of the enduring relevance of the literary works, Nafisi recounts the systematic erosion of personal and public freedoms under the new regime. The unending directives from the state seeking to regulate thought, belief, speech, dress, movement, worship, work, business, relationships, the entire spectrum of its citizens’ existence; the fearsome moral policing, the stigmatisation of the liberals and socialists, the witch-hunt of dissenters, the increasingly hostile and violently squashed standoffs between the regime and its opposition, are all described in disturbing detail. Usurping individual identities and histories and recasting them in the moulds sanctioned by the ruling clergy, banning access to the thought and customs of the world beyond, insistence on the superiority of the morally vigilant Iran over the debased, demoralised and decadent west, became routine. And all through her catalogue of her memories from back then, Nafisi pays particular attention to what it meant to be a woman in a blatantly patriarchal, brazenly misogynistic culture. A dissenting woman, in particular, one who is brusquely squashed back into her designated place of silent subservience. A place from which she may not be permitted even a whimper, but where she can still hold on faithfully to her memories and wander freely in her imagination. Clinging on to those residual arbours to rescue her sanity from the assaults on her persona.

I shudder at the abuse, deprivations and outright atrocities that women have had to suffer through the ages. The world over. The fairer sex, the weaker sex, the gentler sex and other such facetious epithets have been flippantly tossed around as labels for half the population, propping up a rationale to confining women in closeted spaces, restraining their movements, shepherding them around under the watchful eye of their patriarchs. For their supposed protection. Being used, abused, exploited, denied, supressed, treated as mindless chattel, their actual destiny. To reach where we are today, women have had to walk a long hard road inch by painful inch, fighting with grit to be regarded and respected as equal humans. Yes, they have been supported by sane men, those who responded sympathetically to their demand for respect and parity. But those men were few and far between. The women’s movement swelled through the ages, the baton passed on to younger and younger blood, and the struggle continued. It continues till today, as determined women the world over patiently, incrementally win back freedoms that had been malevolently eroded away or had never even been theirs to start with. The restoration of rights to education, to work and be paid, to own, inherit and bequeath property, to vote, to choose one’s own partner oneself, to divorce, to retain custody of offspring, to speak for themselves in their own voice instead of being subsumed under their patriarch’s position, to make their own decisions regarding mind, body and soul, all this and more, has been a tediously slow and excruciatingly uphill battle. A battle that continues. And while in the public domain of the free world, gender parity may now receive credence or at least lip-service as politically correct, in the harsh reality of the private so many women continue to suffer. Galling.

Well, as Nafisi says in her memoir, the revolution ominously regressed Iran back to those dark ages, effacing the cumulus of the inch-by-inch victories that women had perseveringly toted up through successive generations. They were shrouded back in the veil, prohibited from meeting men other than those in their families, their brothers, fathers, uncles and husbands, their only legitimate keepers, owned and directed as chattel, chastised, punished, imprisoned and even executed for refusing to obey the patriarchal dictates spouted by the new regime. There are chilling accounts of how a woman’s fair skin inadvertently peeping out from under her veil was cause enough for arousal, molestation, rape and even murder. Young girls on the cusp of womanhood would secretly paint their nails, style their hair, learn the skills of makeup, vie for the latest in fashion, but bury it all in an all covering chador before stepping out of their homes. Aspirations to being treated as equals were dismissed as mindless aping of the evil capitalistic west of which America was brand ambassador. Bookstores shut shop, publications confiscated, cinema and art lay desolate unless they served to mouth the regime’s propaganda. The betterment of the populace that was the promise of the revolution was at best illusory for the likes of Nafisi.

Reading this while sojourning in California, I cringed at the abject wretchedness of it all. And my mind went back to the uprisings in Iran a few months ago, the heavy-handedness with which the regime came down on the spontaneous protests, the consequent loss of life. Tragic. I breathed easier when I raised my head and saw my surroundings, the genteel suburb in the land of free speech, ample opportunity, and a robust espousal of the shining American dream. And then hesitated. A country that proudly holds aloft the banner of freedom has through the onerous Roe v Wade rudely clipped a woman’s right to make decisions regarding her own body. Choice, choice, choice. Free choice. The mark of a free nation. The core of democracy, the right to choose. Shouldn’t that be an inalienable right? Ask Nafisi.

Nafisi suggests in an interview that the reader bring curiosity and empathy to the book in hand. I think these are important attributes for living life itself. They would encourage us to not merely understand and respect another’s perspective regardless of our own, it would lead us to endorse the other’s equal right to choice as also their right to dissent.

I will soon be returning home, back to my land and people. A land that is lauded as the largest democracy of the world. I wonder, what about our rights back there? And the visual surfaces: a bunch of young women wrestlers, protesting against the predatory advances of their male chief, being summarily hauled away from their protest site and detained behind bars to secure the successful passage of a ceremony of the inauguration of the temple of democracy, the Indian Parliament. Women who had won medals in international arenas, who had been proudly feted as the symbol of the new successful India, now an embarrassing encumbrance, a thorny inconvenience, summarily dumped in jail while the predator walked free. Those other predators too who had raped and murdered, found guilty of these heinous crimes in a court of law, duly sentenced, but were seen winning a special pardon on the nation’s Independence Day. Who on being released were raucously felicitated and then spotted sharing the stage with politicos. Rehabilitated with respect. What of the victims, what of their safety, their independence, their respect?

I shudder again.

And then steel myself. For the battle continues. Onward and forward. Our daughter, that fine young woman with a sterling capacity for intricately nuanced reflection, deep reservoirs of empathy, and a fearless espousal of justice, is a newly minted mother. We welcome our granddaughter into this world. We promise her the moon and the stars. We will teach her to love this world too but will caution her to always be vigilant. To safeguard her rights to liberty, equality, opportunity and justice, rights that have been painstakingly won by a long, long line of women that preceded her. To never take them for granted. For here there is no country for women.

More power to you Rohini for the cause you espouse on all our behalf.

Great piece of writing.

Thank you! Truly appreciate your good wishes!

As always you have through your powerful writing, shone a light on what it means to be a woman in what continues to be a man’s world. While I often feel dejected and angry about how cruel, unsafe & unequal our world still is for women, I get buoyed by the strength, courage and determination of the young women and men of Iran and their sisters & brothers in many other parts of the world who continue to fight for the right to take control over their bodies and their lives. Thank you Rohini for a sterling piece of writing.

Thank you, Aneeta!

These are issues that we feel deeply about, I am grateful and glad to learn more about them from you.

Well relayed thoughts and brilliant piece of writing!

Thanks so much, Siddharth!

Dear Rohiniji

A very powerful peace of writing. Treatment given to women in these societies is despicable. Protests by few women is laudable. But real change will occur if women influence their growing children to be better humans. Can this be done?

Thank you!

I agree, we need to raise our children well. To respect each other genuinely, appreciate the diversity among us and not make that a basis for discrimination.

Truly, as always, your sensitive potrayal touches the core of one’s being. Your choice of words, your intimate style of writing, paints such a realistic picture, that, the only realisation is, that of, being in the depths of the situation. Your writing is certainly overpowering, Rohini ! More power to your pen !!

Generous, indeed! Thank you so much!