Tag: review

-

NO COUNTRY FOR WOMEN

The past couple of months have been especially good for me. Plenty of interesting reading and ruminating, yes, but also simmering excitement about some eagerly awaited news, some personal happy tidings and immense familial joys. My cup runneth over. Of course, the world around and beyond isn’t exactly a happy one and some of its…

-

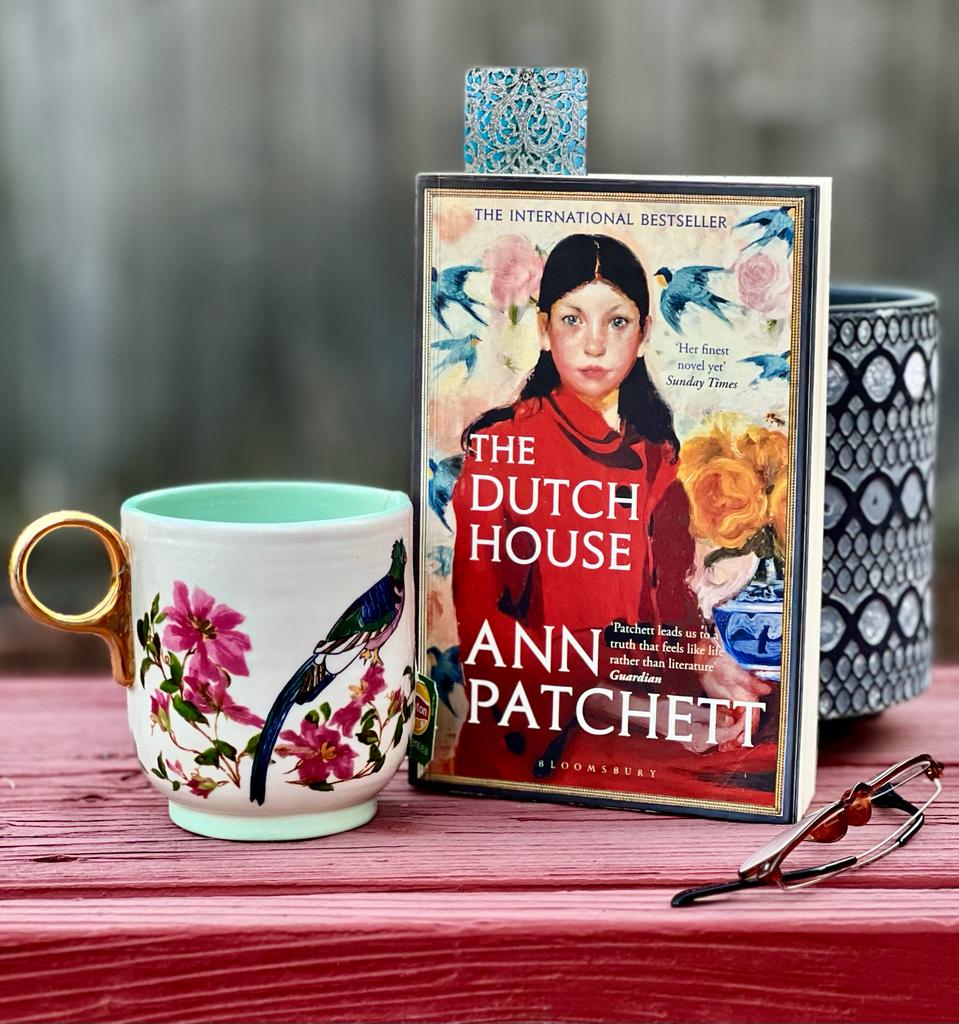

THE DUTCH HOUSE by Ann Patchett: A REVIEW

Everyone’s been raving about Ann Patchett and her fabulous books. A few years ago I had heard of her Bel Canto, how well-received it was, making waves in literary circles, and I had marked the book down for a later read. But then I recently picked her The Dutch House instead, trusting my instincts of trusting an old school-friend’s recommendation! The avid and discerning reader that she is, I often blindly follow her suggestions. And I was amply rewarded. What a page turner!…

-

-

The Sense Of An Ending

THE SENSE OF AN ENDING By Julian Barnes A Review I remember falling in love with The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes when I’d read it a couple of years ago. I also remember realising as soon as I’d finished, that I needed to read it again (which I did for a book…

-

Hamid

—

Oh! What a twisted and tortured world it must be out there in modern day Kashmir. Where truth and lies overlap and blur and lose themselves in each other. Where everyday breaths are stolen against the everyday din of screaming bullets and pelted stones. Where the lakes freeze over the memories of stifled lives and…