Weaving words into

timeless

stories

From the heart of India come stories that transcend borders, connecting souls across cultures and generations.

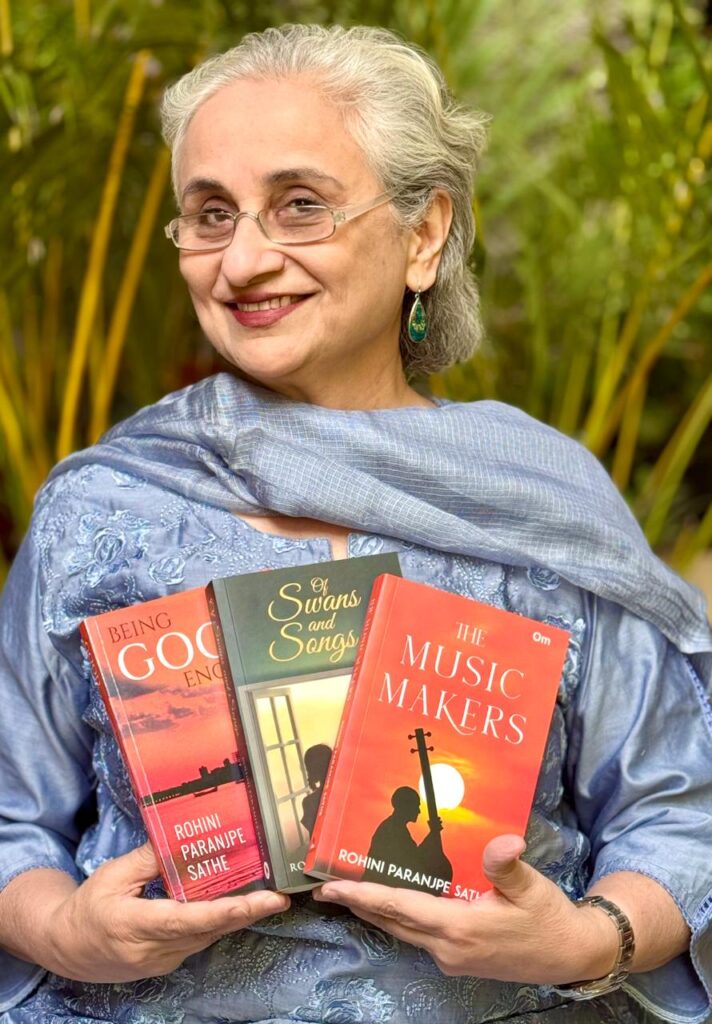

Latest Book

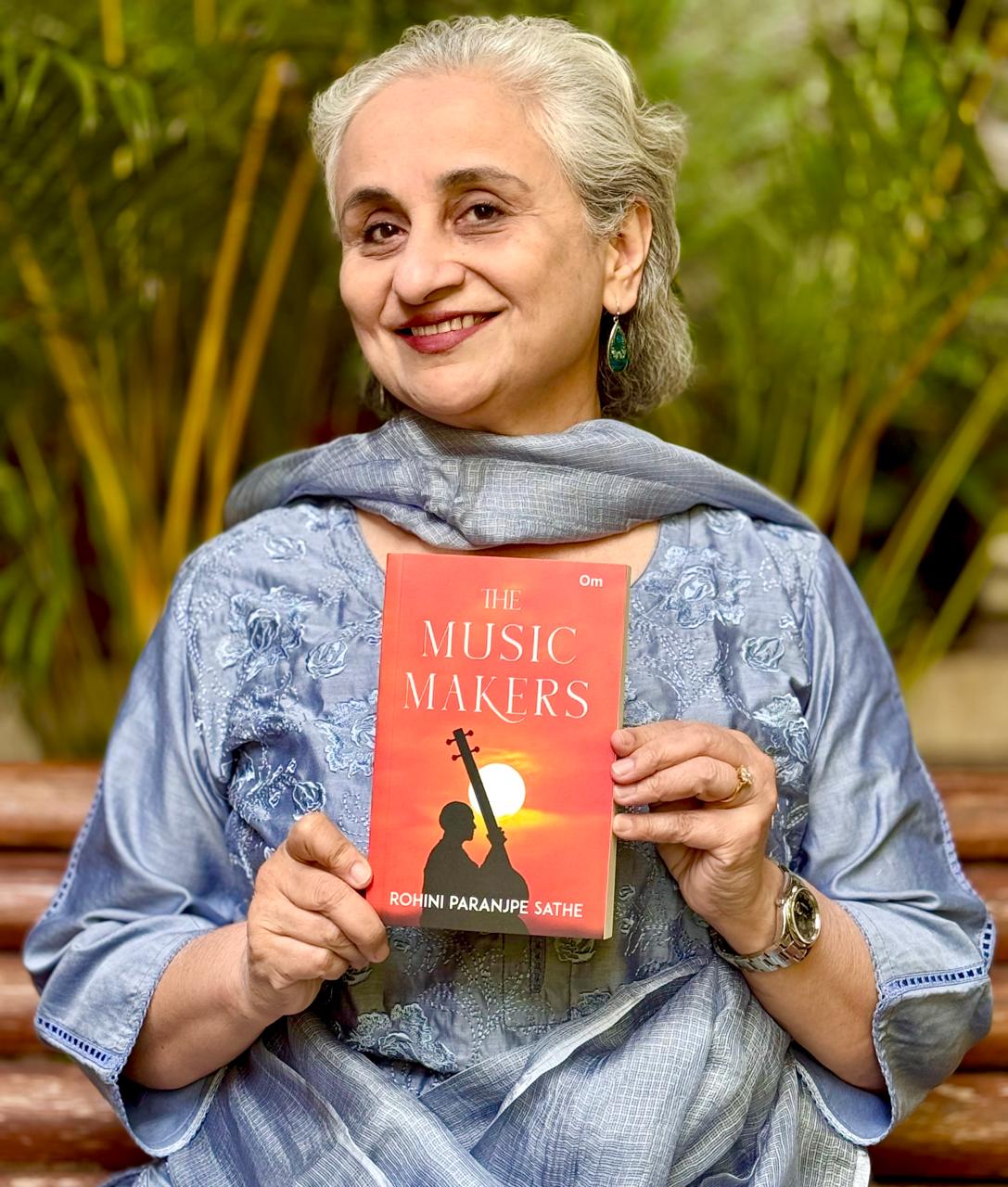

The Music Makers

Padma Bhushan Pandit Sadashiv Buwa Shrotri, a celebrated Hindustani classical vocalist, broods about the future, his own and that of his esoteric art. As he ages, questions of legacy and continuity weigh heavily on his mind, especially in a world where classical traditions are increasingly pushed to the margins. His wife’s nephew, Kartik, drawn irresistibly to the ragas, defies his father’s ban on music. And one evening he disappears mysteriously.

- Published: December 2026

- Pages: 356

- Available in Paperback

Featured Articles

Join the Journey

Subscribe to receive updates on new releases, blog posts, and exclusive content.