It was in the middle of the afternoon on a regular weekday. I was driving to school to pick up our daughter. Well, the car practically drove itself for I was hardly conscious of steering it. It was on its customary route, taking the usual turns this way and that with indicators flashing accordingly, stopping at traffic signals turning red, buzzing through those that were still green, honking a slow scooter out of the way. I registered none of its movements. It was as if all were on auto cruise and my car understood better than to disturb my mood.

The sun was searing from up above, not a cloud between it and the wilting humans beneath. Pelting and melting as was its wont. But I felt it not. For I was in the land of Vrindavani Sarang, in the cooling shade of serene melody, listening hypnotised to those lilting notes and that majestic voice that called upon them with the love that only he knew, suffused with the like love and devotion that he inspired in all us acolytes. The sun was in veritable song. Tum rab, tum saheb, an ode to divinity in a languid loop of the ten beat Jhaptaal.

I had been addicted to that voice ever since my childhood, it echoed from my earliest memories. My parents, both his ardent fans, buying their first LP with his Maru Bihag and Malkauns. Then buying another and yet another with every paycheque every month. As their record collection grew, there came more Ragas that he had sung, and then were added more voices and instruments too. A Pandit Paluskar, a Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Sahib and an Amir Khan Sahib. A Pandit Ravi Shankar, a Vilayat Khan Sahib and a Bismillah Khan Sahib. Our library of music grew richer over the years, my mother carefully choosing the programme for the evening, lovingly removing the jackets and carefully prising out those mysteriously shining dark discs from their sleeves, gently blowing away the rogue specks of dust she spied on them, positioning that sharp needle on the outermost edge and then with breath drawn in in expectation, lowering it to play. Aah!

Rasiya! I would hear that voice call in earnest entreaty and I would listen as if compelled, as if nothing else mattered, as if that Maru Bihag was all that there was of any import. That stoic shuddha ma, the genteel ga, they had become my friends before I even knew them by name. Tadpat raina din, he would confess his yearning for a glimpse of his beloved and I, all of two years old then, would be in harmonious sympathy.

The sun blazed on, my car was at the school gates, children were pouring out. Mine came too, satchel dumped on the backseat, door slammed shut and the music changed from the CD that had been playing to her favourite Radio Mirchi. I drew my car out from my parking slot and drove back home, listening to her excited chatter and the equally animated radio jockey.

Bharat Ratna Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, the lustrous and illustrious gem of India. Swar Bhaskar, the voice of the sun and the sun among voices. Estimable and knowledgeable Panditji. Fond elder Bhimanna or simply Anna. We of this prosaic material world came to know and address that musical giant amongst us according to our closeness or distance from him. I knew him as my first repository of true music, the sachha sur, my own revered musical deity and my reference for all issues melodic. My ears had been trained listening to him right from my cradle. My sensibilities musical had been defined by him, resolutely in favour of the leisurely build-up of a Raga’s ambience in its khayal, the sombre and stately alaaps progressing measuredly against the protracted dhin dhin of the favoured ektal on the tabla, graduating to a quickened tempo and traversing through all three octaves in boltaans and taans, some in blinding speed, simple or complex, rolling with rumbling gamaks or cutting through like flashes of lightning. I was already familiar with it all before my formal training in Hindustani classical music commenced. And while I enjoyed the five-minute film songs that ruled the popular roost, I found that their flavour faded soon. In contrast, the Ragas that the maestros sang sustained and endured, resounding and resonating long after their last tihai.

I remember a concert from many, many years ago, a private mehfil that I had been privileged to attend along with a few dozen invitees. Bhimsenji had begun with a Darbari Kanada. Diving in introduction into the well of the lower octave, that all important mandra saptak in Darbari, he had at once drenched us all in its thick swirling currents. Enunciating each note with polished precision, clarity and mellifluousness, then blurring and merging them in gliding meendhs and Darbari’s trademark andolans or oscillations, and then standing poised and still on the bedrock of his reverberating kharja, he had woven his magic over us all, connoisseurs and laypersons alike. Then climbing up through the middle and higher octaves, steadily approaching and gathering in every successive precious note, he had structured layers and layers to that magnificent edifice of his khayal. Regal and assured yet deeply introspective, melancholic in some phases, caressing tenderly in some others phases, supplicating piteously in yet others, it was a continuing alchemy of overwhelming emotions and I listened mesmerised. His voice, the most robust that I have ever known, would roar in command and then whisper in intimacy and then again plead in all humility. There was heroic power, abject pathos, stark asceticism, all in a glorious and wondrous mix, transporting us to rare other-worldly bliss. I had forgotten myself, forgotten my surroundings, rapturously lost in the darbar of his majestic muse. I doubt any other singer I have ever heard could match the impact of that night’s rendition. It washes over me still. Darbari was his, his alone.

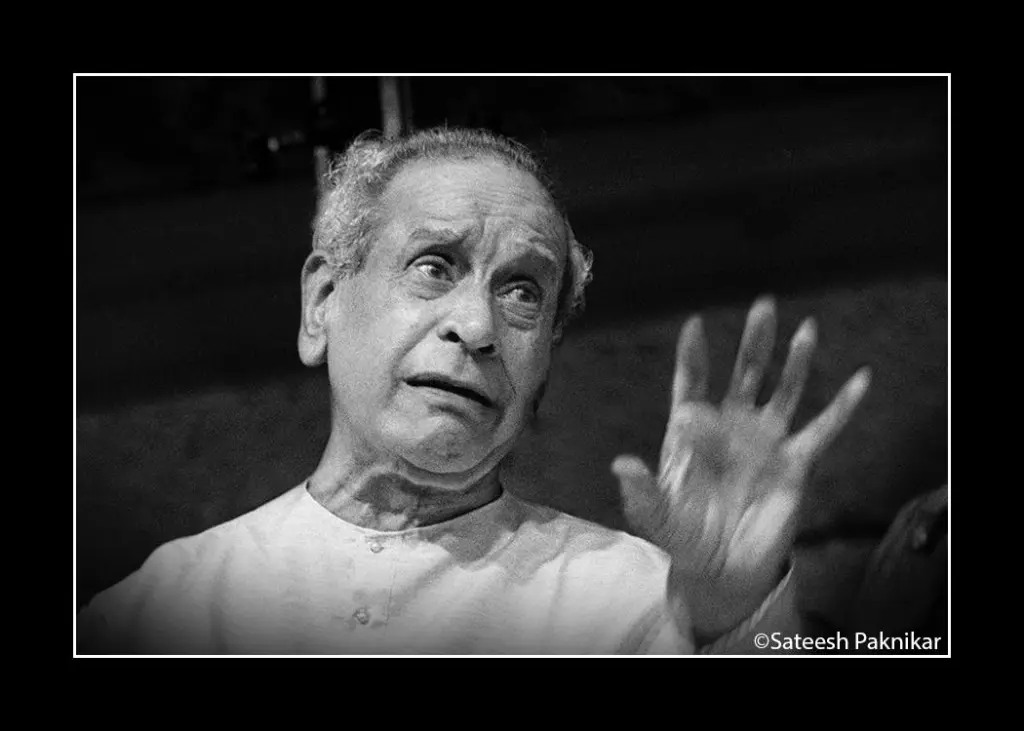

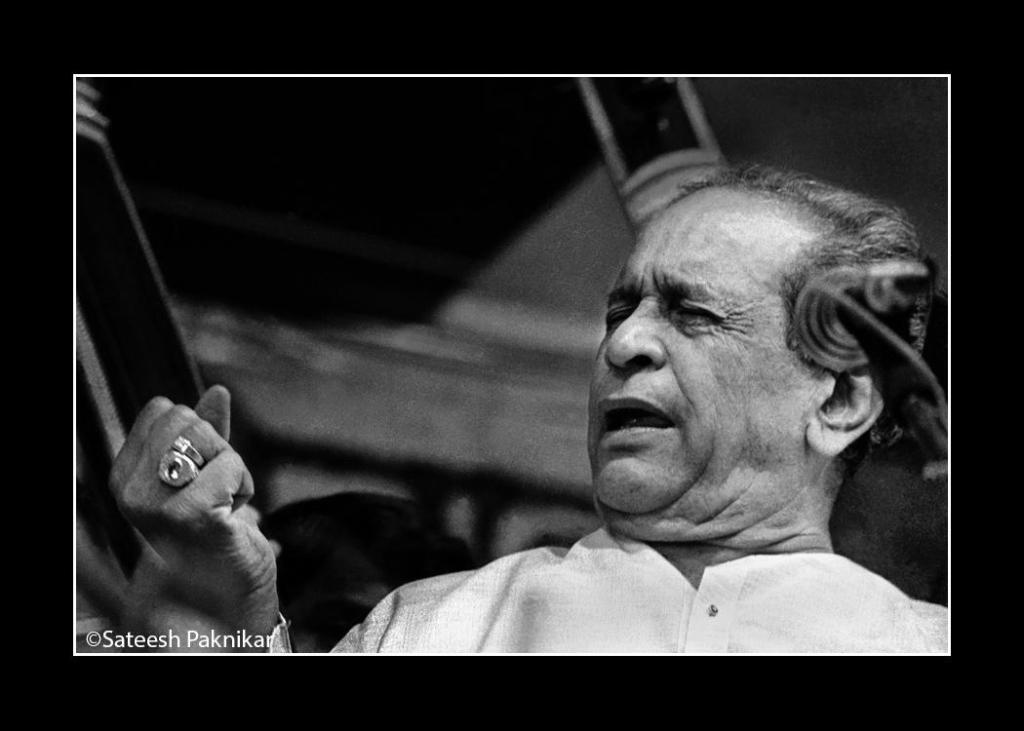

But then so were Puriya, Marwa, Shuddh Kalyan, Mian Malhar, Miyan ki Todi and many more. Yes, I enjoy and follow other classicists’ interpretations of these Ragas too but I still return to Bhimsenji, not merely from fond nostalgia but with a sure knowing that in him I will find only the Raga in its purest and most sublime form, not a projection of he himself or his prowess. Whenever he sang it seemed as if he, his voice and body as also his spontaneity and virtuosity, were all possessed by the Raga itself, commanded unto its bidding. And the bizarre contortions of his face and torso and arms that became his caricatured personality, were simply in driven blind-eyed pursuit of the next magically musical phrase.

Some of his contemporaries and critics would denounce the limits of his repertoire: “He sings the same few Ragas everywhere! And the same thumris and abhangs.” And his loyalists would bristle in anger: “No, his repertoire is wide enough! His reach in every Raga is the most profound! And his Teerth Vitthala is matchless!” Well, all I knew was that his every performance in any given Raga would be different every single time, revealing this face of a Miya ki Todi today, for example, another tomorrow and then yet another the day after. Yes, like all other artists he probably had his share of off days too, when his heart and mind refused to apply themselves to the Raga at hand, his mood refusing to submerge into the Raga’s, when magic refused to happen. And yet there are priceless recordings of a Yamani Bilawal or a Multani or again a Komal Rishabh Asawari and many more that I play and replay again and again, for days and months on end, unable to escape that magnetic pull, unable to pack in not only the strength of his notes but also the golden honey-like Kirana gharana sweetness that he doused them in.

Two of my uncles had been privileged to be among his friends. Doctors by profession their hearts, I suspect, beat happier in tandem with the tempo of khayals and bandishes. I would be hungry for all the interesting anecdotes that they had to share, tales of his sharp wit and mischievous humour, of historic benchmark performances, of hobbies and interests. I would read all I could lay my hands on, his interviews, the stories about his formative years, his crazed obsession with music, his scouring through the length and breadth of the country in search of a Guru. The rigorous discipline and arduous training under the famed Sawai Gandharva, the Guru he was blessed to find, his long hours of gruelling riyaz, the swallowing of personal pride and notions of privilege to be merely allowed to remain in the vicinity of a handful of melodious notes, the unswerving loyalty to his Guru. His rapport with other luminaries of the music world, his encouragement to young artists. The commitment and dedication with which he organised the annual Sawai Gandharva music festival, inviting both established maestros and upcoming artists, looking after their comfort, tuning their tanpuras, listening to them in humble attention while they performed. And then capping it all with his own magnificent performance in the last session of the last day, his resplendent homage to his departed Guru. I devoured it all. I learned of his eccentricities, his failings too, but I judged him not for his human frailties. For all I ever saw in him was his divinely sachha sur, the sur that continues to reign supreme.

The sun still sings for me. He still propels my day forward, guiding me through its gradually changing texture and complexion, showing me the fledgling streaks of orange in a day-breaking Lalit, a little more of light and warmth in a Ramkali. At burning noon, he coaxes me into the resuscitating shade with his Sarang, then shows me the morphing world in the evening’s Puriya Dhanashri. Later, he slips away beyond the horizon leaving me the riches of a Bihag, a Yaman, a Chhaya, an Abhogi, many and much more to revel and rejoice in, to nourish my searching soul.

Many sang after him, many stake ownership of the stage, many have won millions in audiences and admirers. Yet to me none can hold a candle to him. The singularly luminous star that burned so unbelievably bright that he lit up all firmaments, the earth, the sky and the universe beyond. The one and only Swar Bhaskar.

Photo Credits : Sateesh Paknikar

Beautifully penned

Thank you, Swati.

I was transported to another world with your sensitive, soul stirring write up which I so thoroughly enjoyed.

Rarely does one find something so richly written , and heartwarming.

Wow! That’s amazing! Thanks so much!

Wonderous words to illustrate a genius artiste….

Thank you, Raju!

When you write about music, you take us, your readers, into another realm, Rohini. Thank you for providing an uplifting start to my day

I suppose music (any art, for that matter) does that to one when there is passion for it and commitment to it. That passion will tell.

खरं तर वसंतराव माझे फेव्हरिट. पण तुमच्या अप्रतिम लेखाने भिमसेनना परत ऐकण्याचा हुरुप दिला.

Beautifully written. Written as competently as the style of the maestro himself. It was just as poetic as knowledgeable.

That is generous praise. I am humbled. Thank you.

I wish Anna could have read your ode to him. Appreciation from the heart is the greatest gift that you can bestow upon a musician. Joy when you sing for yourself, great joy when you sing for others , even greater joy when you have them enraptured .

I sometimes think that the best music happens when you sing for yourself. And I suspect that these maestros were well aware that they were chosen by the muse herself to pursue and present the art and they did that regardless of who was listening. They often lost themselves in a trance spun by the Raga, that we were enraptured too was a happy corollary.