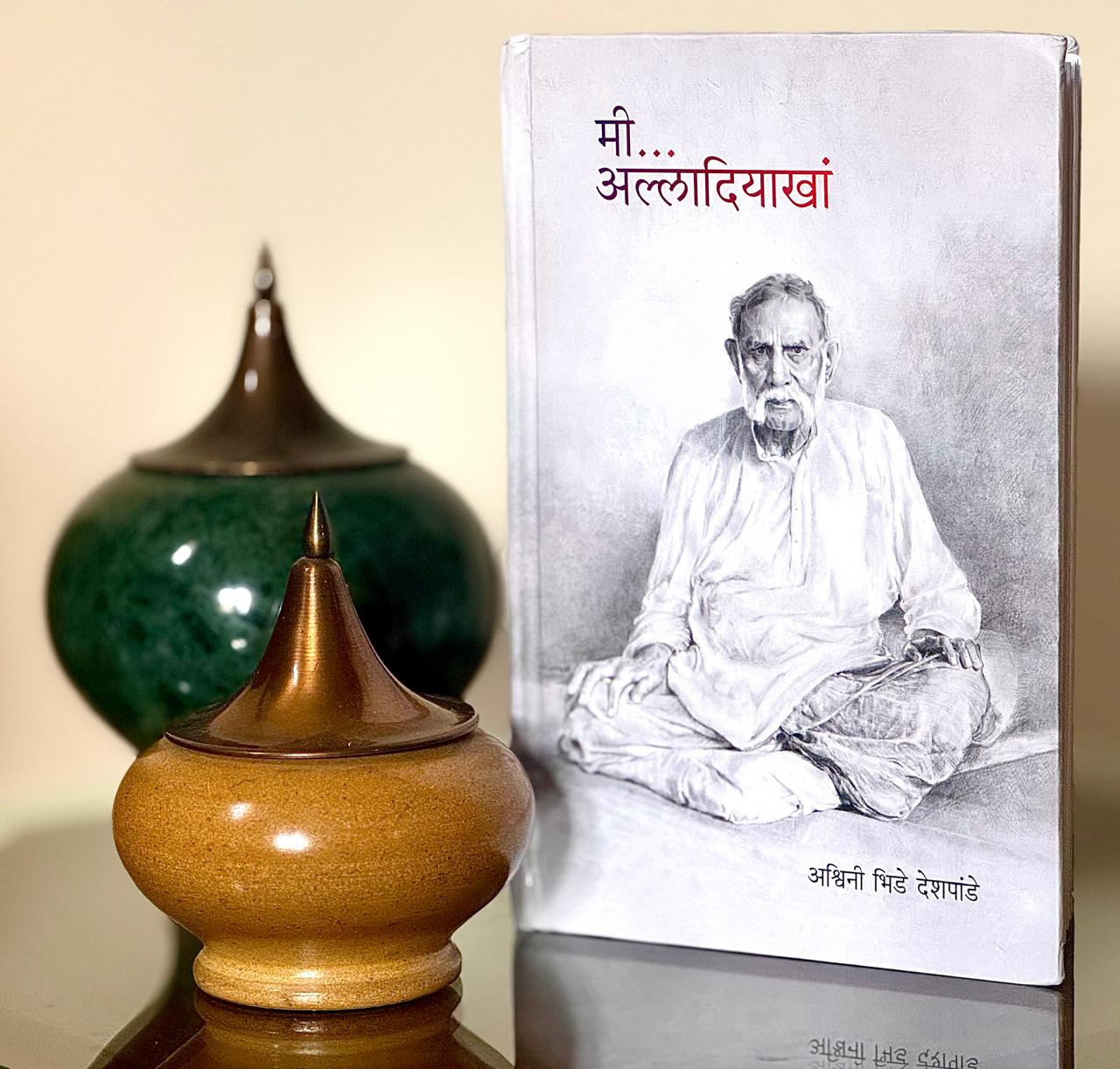

Mi… Alladiya Khan

This is Ustad Alladiya Khan Sahib’s life story, written in Marathi by one of the best classical vocalists we have today, Ashwini Bhide Deshpande.

There were a few reasons for this reading choice:

First, Ustad Alladiya Khan’s stature in Hindustani classical music is legendary. As the venerated stalwart of the Jaipur-Atrauli gharana, innovator of a mesmerising vocal style, composer of numerous beautiful bandishes, and guru extraordinaire having faceted and polished several gems of our classical tradition, I was instantly drawn.

Second, Ashwini is one of my favourites. There is a profound musical pool that swirls beautifully within her, sometimes masked by the beguiling simplicity of her stage persona. She has learned from the best and accessing and maintaining the best standards in her art appear to be her enduring goal. I’ve been listening to her for years and have always felt satisfied that the raga of her choice was given justice. Her musical aesthetics, her ability to immerse herself in the emotional ambience of the raga, her refined skills that she draws upon only in the raga’s service, enhancing its personality, all bring great joy. That she would bring these values to her portrayal of Khan Sahib was a happy expectation.

Third, this is written in first person, as if the author inhabited Khan Sahib himself and recorded his life and career in his voice. Which makes it an interesting literary exercise, considering also that he passed in 1946. Yes, published biographies and other resource material must have been exhaustively combed, but it is that intimate personal touch that lured. Further, Ashwini asserts that this is a ‘lalit’ presentation: that while staying true to documented facts, she has used a measure of her artistic licence and liberty in narrating Khan Sahib’s life to render the reading more fluent and, as I found, rewarding.

Ustad Alladiya Khan Sahib was born as Ghulam Ahmed in 1855 in Uniara, Rajasthan. But as the sons born before him perished soon, his parents fondly called him Allah ka diya, a gift given by God. The name stuck.

His early life – the large joint family bustling about under one roof, shagirds coming home for their musical taleem, the daily riyaz by his father, Khwaja Sahab, and uncles, Chacha Jehangir Khan and Chimman Khan, with Alladiya sometimes falling asleep on his father’s lap, lulled by the singing – was fascinating to read. The early demise of Khwaja Sahab; Chacha Jehangir Khan taking young Alladiya under his wing and training him rigorously for a career in vocal music; the hours of practice, the dhrupads, dhamars and khayals that were learned assiduously, the anwat ragas (not frequently sung) that came to him as his gharana’s legacy – Ashwini describes all, faithfully.

Alladiya Khan’s life progresses well though not without its share of hiccoughs. There is an instance of a musical stumble while accompanying his Chacha at a public concert in Ratlam, for which he is rebuked, publicly. But instead of sulking, his artistic integrity urges him to accept the rebuke as deserved and firms his resolve to do better. Some contemporaries disparage him, but he stays undeterred on his path. Sometimes an accompanying percussionist attempts to humiliate him, but Alladiya’s natural camaraderie with taal and laya helps him put the baiter in place.

His singing matures with his unstinting riyaz. Every facet of his gayaki is polished: the gamak, meend, taan, layakari and more. He realises early on that a raga’s emotional core is its true identity, one that can sometimes move us to tears and he aspires for that asar (impact) every time he sings.

Travelling through north India, he enjoys the patronage of royal courts, sometimes struggles with material hardships, loses a gurubandhu to an instigated rivalry. He rarely loses heart, notching every life lesson under his belt as he ripens into one of the sought-after vocalists of his time. After a euphoric week of spell-binding concerts at Amleta, Alladiya discovers to his sore dismay that he has damaged his singing voice. Only prolonged rest helps heal his vocal cords and after deep introspection he begins to alter his vocal style, developing his own gayaki that later becomes the hallmark of his gharana.

After years of travel, he returns to his native Rajasthan where he is well looked after by Rajput royalty and nobility. Jaipur, Jodhpur, Udaipur have already witnessed his ascent as the most esteemed representative of his gharana. And then the Ustad turns south.

After his enthralling performances in Baroda and Mumbai, Khan Sahib is offered an appointment as court-musician by Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj of Kolhapur, an offer that he accepts gratefully and graciously.

This marks the beginning of a new chapter in his life, a substantive spell of more than two decades during which he sings for the Chhatrapati’s court and the Devi’s temple, at festivals and for visiting dignitaries, and intensively trains his disciples. His younger brother Haider Khan religiously shadows him everywhere, more his shishya than bandhu. He teaches his sons who take his tradition forward. There are more students, including his best disciple, Bhaskar Buwa Bakhle, who like a true mirror, absorbs and reflects his guru’s music. Bhaskar Buwa popularises the Jaipur gayaki, taking it to the common man in Maharashtra, setting the music of Marathi plays to the traditional bandishes of his gharana. Khan Sahib’s heart feels full.

Later when he shifts to Mumbai, he gains two outstanding shishyas. The diva Kesar Bai Kerkar whom he trains exclusively for nearly ten years, catapulting her to stardom in musical circles at the end of her tutelage. And the stellar Mogubai Kurdikar (Kishori Amonkar’s mother) who gratefully gathers every swara and matra that fall from her guru’s lips, working upon them with virtuous diligence, making them her own and achieving divine mellifluousness.

The deaths of Bhaskar Buwa, Haider Khan, his son Manji Khan and his beloved patron Shahu Maharaj, come as crushing blows. There is an instance when, during a performance, he breaks down crying: his loyal Bhaskar who accompanied him at every performance, who sang with such feeling and finesse that it gratified his guru’s heart, has just passed away and Khan Sahib misses his presence behind him on the tanpura. He feels cheated that while he lives on, those he loved died much younger. But his art abides by him, continues to stir within him, and he consoles himself by returning to his ragas, knowing that they remain his steadfast life-companions.

This book was a wonderfully captivating read. It is replete with intricate detail, successfully resurrecting the era it is set in, the world it portrays. I can see the grandeur of courts, the cognoscenti recognising and applauding the artist’s merit. My heart feels warmed by the bonhomie among fellow artists, sometimes learning from each other. I sneak into concerts to listen to Khan Sahib in all his resplendent glory. I see other famous Ustads in attendance, Faiyaz Khan, Natthan Khan, Rehmat Khan, many more legends that I grew up hearing of, all nodding in appreciation of Khan Sahib’s prowess. I hear the tanpuras strumming and the strains of his ragas, the Nats and Khat, the Kanadas and the Todis. I sense the thrill of a perfected taan, the emergence of a new bandish …aah! Ashwini writes it all so evocatively that I lose myself in that world.

There is a natural poise, a natural flair to her expression and this book is testament to her multi-faceted artistic being. There is careful thought and heartfelt sentiment in her writing, much as in her singing, marrying art and artistry in soulful union. She dwells on the essentials of Khan Sahib’s gayaki with such fondness that we know that they are invaluable to her as well. There are many interesting snippets, anecdotes and observations that add depth to the telling. As also an artful interspersing of Urdu through the Marathi text, persuading us that this is how Khan Sahib thought and spoke. There are light-hearted moments, some of gravitas, poignant ones too. Her referring to Khan Sahib’s khayal composition in Alaiya Bilawal, Kitwe gaye logwa, when he mourns the loss of his near and dear, is extremely moving. And that a practising Muslim devotedly sings in praise of Hindu deities is a resounding endorsement of our music’s secularity.

What I missed were some personal details. I see Khan Sahib as a musician par excellence, as a disciple honing his craft, as a giant among contemporary vocalists, as the most sought-after guru. But rarely as a son or husband or father; in particular, there is almost nothing about his relationships with his mother and his wife. Ashwini says in her concluding thoughts that she had no reference material for delving into his personal domain. Perhaps, the demarcations between public and private were more stringent then, and we know him only as the illustrious doyen of his gharana.

There are scant allusions to the British Raj or to the independence movement, though Khan Sahib’s life spanned those tumultuous years of our history. But he is described as apolitical, disinterested rather, and that while he notices the British military camps on the outskirts of Delhi or knows his son is participating in protest marches, his attention never seems to be drawn there.

There are repetitions in a few places that led me to suspect that some chapters may have been written as discrete pieces.

There is a plethora of names, a rollcall of musicians from back then, some that I didn’t recognise at all. But this is perhaps me nit-picking.

For this book is so well researched, so well composed, so evocatively written, that I have no real complaints at all. In fact, it sings like a majestic khayal, its successive chapters tracing the maestro’s journey through life in structured badhat, its drama unfolding in measured pace with due aesthetic embellishments. I hum along, sway too, and nod at the sam. I feel enriched. Grateful that I could see this towering genius from up close, a century after his time. Understand the irrefusable call of his art, his unswerving devotion to it. And be grateful that he painstakingly built a legacy to bequeath to the generations that followed. That it reaches us today in the here and now through his luxuriant gharana-tree. And that Ashwini who sits with compelling grace on its robust branch, still regales us with it, keeping her Jaipur-Atrauli tradition vibrantly alive.

Leave a Reply