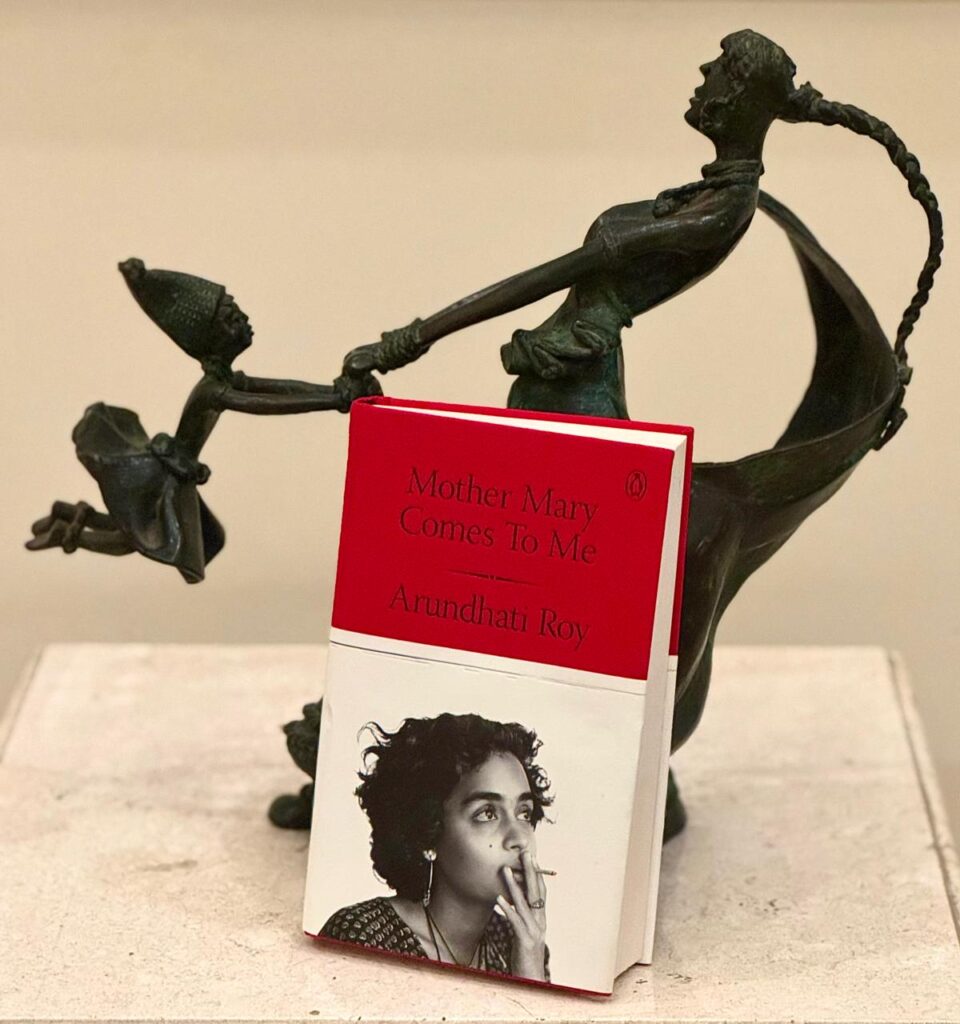

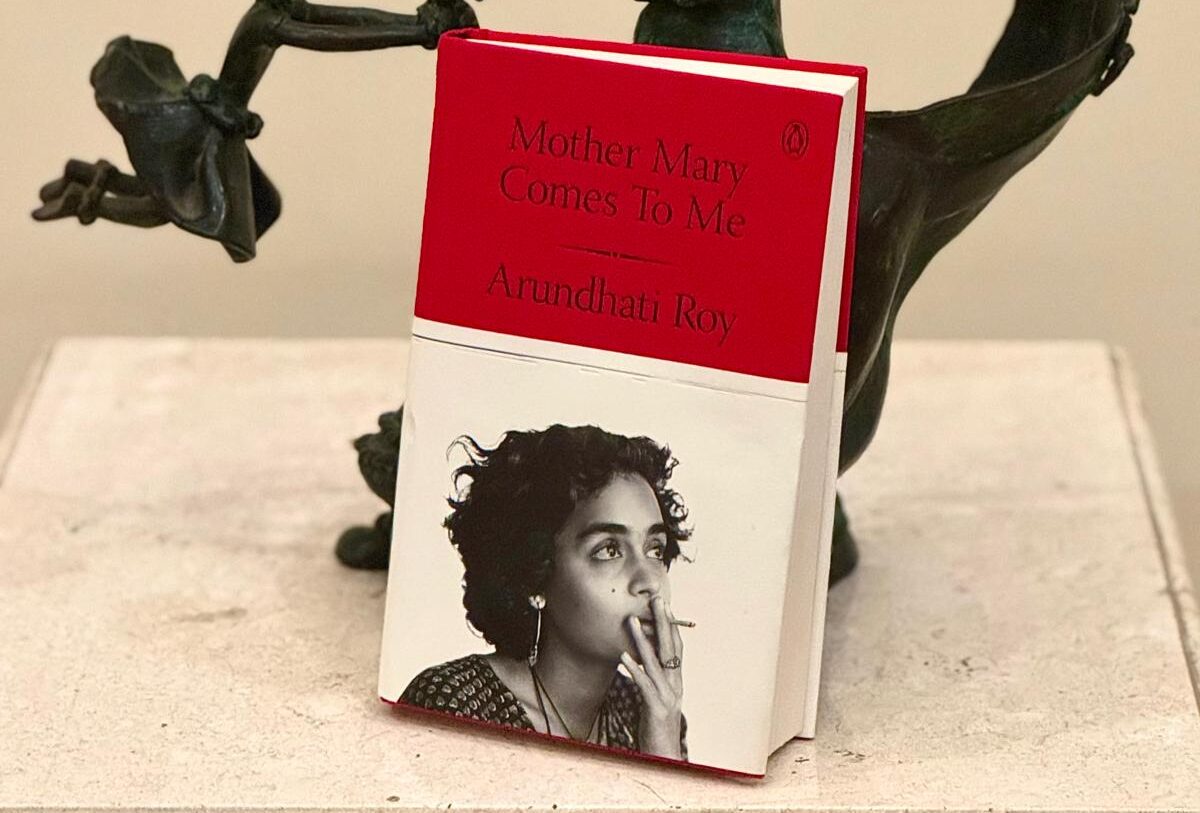

I read Mother Mary Comes To Me like a possessed monkey. I shirked some work, skipped some chores, and died to come back to its pages every time I had to step away to do something else.

That is the magnetic pull of Arundhati Roy’s writing. Is it perfect? Not at all. Like every thing of beauty, it has its flaws. Warts too maybe, some trite moments, yes, and I frowned at the parts where I suspected the crafting of a veneer. But I could not stop reading. Not even pause to linger over and slowly savour what she had written.

As the publicity blitz surrounding the release tells us, this is a memoir. Of Arundhati and her mother, Mary Roy.

Roy senior is Ammu, and Arundhati and her brother, LKC, are the children in The God of Small Things. And while I had read and unequivocally loved that book many, many years ago, some of its episodes and descriptions were jerked alive again in my memory. The God of Small Things clearly drew a lot from her own life growing up then in Kerala.

No mother-daughter relationship is perfectly and completely harmonious, I know none such. While there is love there is invariably some pulling away too, some pushing against, some grudges, some guilt, sometimes a falling apart however briefly, some friction or the other. But the one that inhabits these pages is denser than all of that, peculiarly so, volatile too. Roy senior, or Mrs Roy as her daughter calls her, was a tyrant, a cruel one at times. Puzzlingly loving too at times. Arundhati says that LKC suffered most of the brunt of her cruelty. Not that Arundhati was spared. She talks about her mother’s asthma, her dependence on the inhaler, her need for steroids as well, her unpredictably swivelling moods, her ballooning anger that matched her ballooning body, her beating, berating and insulting her own children, even when they were small and practically defenceless. Get out of my house, was apparently a refrain. Shudder.

I was particularly saddened by her description of how LKC, not a good student and getting poor report cards, would be beaten inhumanly, while Arundhati, a good student with a good report card was praised with affection. That juxtaposition remained embedded in her mind and every time she was feted for something, she feared someone else was getting beaten. Resilient scar.

But Mary Roy had substance, formidable substance. Formidable courage too. As a divorced woman (she would dismissively refer to her alcoholic no-good husband as The Nothing Man!) who refused to be chastised and subservient, she was shunned by her Syrian Christian community. To them she had done the unthinkable: marrying outside the community and then getting divorced within a few years. She became a teacher to earn her livelihood and then boldly founded and nurtured her own school for children, enrolling hers there as well. She fought to strike down the succession law that denied Syrian Christian women the right to inherit property. For she never forgot how her brother had sought to oust her from her deceased father’s house in Ooty where she had taken temporary refuge after leaving the Nothing Man. She battled hard and long and won. These feats are testament to her tremendous will and her fierce streak of independence. They are her lasting contributions to society.

That Arundhati could see, admire and love this side of her mother, that she could accommodate her whimsical cruel despotism, sometimes ascribe it to the flare-ups of her asthma, so much so that as a child she wanted desperately to be able to breathe for her, only shows how strong though twisted that umbilical cord was. A cord that sustained even after she declared Enough! to the near-traumatic abuse and exited her mother’s house. Sustained until her death and even beyond.

That fractious relationship made Arundhati the independent woman she became, independent of mind and means. Of voice and words. Mary Roy’s shadow loomed large over much, perhaps hovering within her, judging her. She understood her own vulnerabilities while sympathising with the fragility that lurked behind that bulwark of her mother.

Her own life, her choices, the men she fell in love with, the jobs she ground herself at to survive, the deprivation she struggled through, the friends she made and treasured, the films she worked for, the causes she espoused at considerable danger to herself, the books and political essays she wrote: all those accounts are fascinating to read, even though some of that is already in the public domain. There are poignant instances of personal pain and heartbreak, instances of triumph and euphoria, of natural ebullience and tender love. Of mulling and reflecting and arriving at a stance, an opinion to uphold. And then walk the talk. I have always admired her ability to articulately formulate and defend her thesis in all the causes she lent her pen to. I believe in some of those causes myself. So, while reading this memoir, while a lot was familiar to me, I still had that pulsing admiration. Sometimes reluctant admiration. Why reluctant? Will explain in a bit.

Arundhati is a superbly gifted writer; she reaffirms that in this book. While I had been blown by The God of Small Things, I had been disappointed by her Ministry of Utmost Happiness. A lot of it I felt was contrived, stretching credulity on occasion, and many passages felt like she was on a rant. Venting, venting, venting. She also has this weird predilection for building a pithy caustic line and returning to it time and again as a motif. Not to my liking. This happens in the memoir too. Her facile glibness as she calls it that she says characterised her when she was young, is apparent in some places in the writing here as well.

But these are like the blemishes we see on the moon, only enhancing its endearing beauty. What impressed me most is her natural talent for grabbing the reader’s attention from the get-go and never relinquishing it. She grabs your sympathy too, you indulge her at times, but not undeservedly. Her writing is strongly visual, even a transient trace of an intangible emotion can be seen and felt and understood. Her brilliant imagery, Aah! her drawing convincing though curious parallels, creating startlingly beautiful and sometimes outright funny similes (old Kurussammal looked like a little raisin wrapped in a saree), minting new metaphors, and just her powerfully evocative language in recreating and bringing to us this little bit and the other from her life. There is exaggeration, yes, frequently, clearly for effect, that I recognised as unnecessary, but could allow for as her writer’s licence. Her observations are so profound at times; the fish and the river lines that she writes after winning the Booker, for example, or then the remark that small money is always subversive. Sometimes hilarious, like the little snide aside about being labelled a writer-activist, reminding her of the ambivalent duality of a sofa-bed.

What resonated with me deeply was her confession that before she started writing she needed to discover her writer’s language: ‘Language that I used, not language that used me.’ And that until she had found it, she stalled. Then as the train of small things came to life and chugged through her, she rode it with fidelity to birth her first book. Bang on.

As with memoirs that shake out closeted skeletons, one may question the need to pour all that private unpleasantness for public consumption. One may deem it unseemly. Why unveil the darkness that dwelt in her mother, that too after her death, when she can offer no defence. But I have none of those questions. That is her choice, take it or leave it. For me, on balance, Mary Roy is terrifying, yes, but strangely lovable too. I credit Arundhati for loving and writing her like that.

But then, here’s the thing: she always defends herself, justifies all she thought, said, did, comes off as the better person always. The superior person. Is she, really? The incurable sceptic in me asks. Often. Even when we may think she has erred, she explains it away so that we want to forgive her. Clever. She showcases her sarcastic wit, derides every opponent with it, wanting to influence us if not by the justice of her position that she believes unassailable, then by the power of her intelligently scathing ridicule.

That sceptic in me also asked: Is this truly how it was? Exactly and entirely? I know not. I am not privy to her life. I am but one of her many lay readers.

As the writer of one’s memoir, one is understandably biased towards oneself. Not just as a writer, as anybody. I think it takes a different kind of courage to peel away that bias and see the truth that lies beyond, understand it and understand how our personal bias could have been prejudicial to it. And a deeper courage of that different kind to admit to that truth on paper for the world to read. And judge.

Of course, there is no obligation to do so. And what is truth after all, one may well ask. Is it absolute in itself? Or a nebulous ideal, amorphous too as everyone feels entitled to their own version of it, their own truth. This is Arundhati’s. Let it be.

Leave a Reply