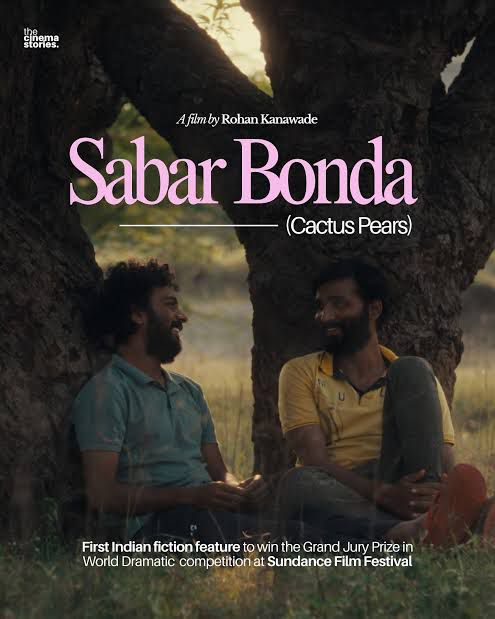

Sabar Bonda, Rohan Parashuram Kanawade’s directorial debut, is a recently released Marathi film about gay love, a love that still hides shyly in closets. It comes commended by critics, winning a few awards at film festivals – one, notably, at Sundance.

Anand is a young Mumbai man who loses his father to kidney failure. He and his mother return to their native village to dutifully perform the last rites. The dos and don’ts that are prescribed for the thirteen-day mourning period are strict: no wearing black, no footwear either, eating only twice a day, never asking for seconds, no washing hair, no returning to work until the end of the stipulated mourning. All rattled off as incontestable givens.

Anand internalises his grief, coping with it the best he can. And to get through the long days that stare bleakly ahead in this forced sojourn, he hangs around with his once-good-friend, Balya. He accompanies him as he milks cows and herds his goats to graze. It seems like a very simple life but, of course, there are pressures. Farming, milking, shepherding, they don’t pay much. Not at this micro level. Plus, there is the inescapable social nagging: why do you refuse marriage proposals, why is no girl good enough for you? The marriage question dogs Anand too, but his mother prevaricates, fending off inquisitiveness with a convincing ruse. She knows her son, as did his father, and there is a fierce urge to protect him from the relatives’ and neighbours’ cruel judgement.

The old attraction between Anand and Balya resurfaces and they long to be with each other, not just to assuage their starving bodies but to find refuge in that tender love that is awakening. They share covert glances when amidst others, and tentative embraces when by themselves. Anand, heartbroken from a prior failed relationship, begins to heal and his mother is relieved. She knows about Balya too.

This is such a poetic film really, one moment flowing into the next in leisurely quiet, all in gentle rhythm as if Kanawade himself is lulled into that pastoral pace. There is no drama, no overly big or loud moments, all in even tenor. Yes, there is a noisy outpouring of grief, a gaudy collective wailing, as the ambulance reaches the village and the father’s body is carried out. But that subsides quickly, is followed by a dull, silent acceptance of loss and a swift shift in focus to the rituals. The grief that harbours within remains within, private; the outward face is composed, stoic. An ugly quarrel that erupts later and whirls about for a bit, is also shushed soon enough, and the village returns to its near-placid groove.

The script, direction and camera staunchly adhere to a showing-it-as-it-is, neither embellishing nor glossing over. The typically brown-green landscape of rural Maharashtra, the thin, nearly bald pastures, intermittently dotted with stunted trees and thorny shrubs. The river flowing prosaically, its banks almost bare. Nothing lush or extravagant, yet beautiful in its eloquent truth. The cremation shed, the houses, the temple, the mud roads, the gutters, all as is, nothing romanticised. The weather-beaten, lined faces, dour expressions in some. The clothes repeated throughout, the same worn-out tees and sarees. No, poverty isn’t showcased, it’s just there. See it, don’t, it hasn’t gone anywhere.

Yet in this rustic, spartan simplicity, there are mobile phones, networks too clearly. These selective modernities that come from the world beyond seem to have been absorbed into their life and landscape. Pragmatic expedience: available, useful, used. Materially upgrading how they (or some of them) work and live. But women still grind masalas on stone, squatting down on their haunches; some give up professional training and careers to manage homes after marriage, willingly too. For the village’s heart remains embedded in its die-hard conservatism, beating in sync with its anachronistic customs and conventions, its unrelenting dictates on what behaviour, what fraternising, what consorting is acceptable, what is not. Not ceding a whit.

The entire cast seems to be rooted in that milieu, belonging to it, as if literally picked from it. All speaking the dialect with ease, making me wonder whether a diction coach was even required. Anand, of course, shows that twinge of city-bred speech, as also some urban niceties, the thank-you and sorry that typify our city-work-culture. Yet nothing about him jars as he fluidly blends back into the rural ambience. He, Balya, his mother are laconic in language, of body and speech, and yet they successfully convey the flux they are going through.

There is no background score, thankfully. No violins serenading or encouraging fledgling love, no funereal sarangis lingering over loss and grief. The solitary piece of music that is heard comes from the temple, where the village gathers to sing to the lord as is their wont, with only their few familiar instruments and their pure, unadorned voices. Beautiful.

Yes, at times I felt the camera lingered moments longer than necessary. Editing could have been tighter, neater, the pace notched up a teeny bit perhaps. But I am not complaining. To an uncompromising critic there may be more lacunae: nothing may seem to happen in some scenes, nary a word spoken at times, some repetitions too. But that is in the very nature of everyday village life, I suspect, the inescapable loop of its muted routine. Its watching-grass-grow. And Kanawade’s letting that new love grow, giving it due space and time, allowing it to find its roots, take hold, sprout shoots if it can, all organic.

This is, above all, an ode to love. Beautifully, quietly lyrical. Queer though it may be branded by censuring conservatives, it is sung with such delicate tenderness, such heartfelt respect, that I flowed with it as if it were the most natural verse on earth. And like Anand’s mother, I too wanted that boy to be fulfilled. To love and be loved in return. Happy mutuality.

Sabar bonda: cactus pear, a thorny fruit, lush within.

Leave a Reply