Author: Rohini Paranjpe Sathe

-

On GRIEF

This I know. Grief is hard. It hurts, it overwhelms, it suffocates. From the moment it appears, it seeks to settle in. A nebulous entity at first, unformed, unknown, unarmed. That slowly begins to feed on us, our mind and memories, our love, loss and longing. Then growing at its own pace, on its own…

-

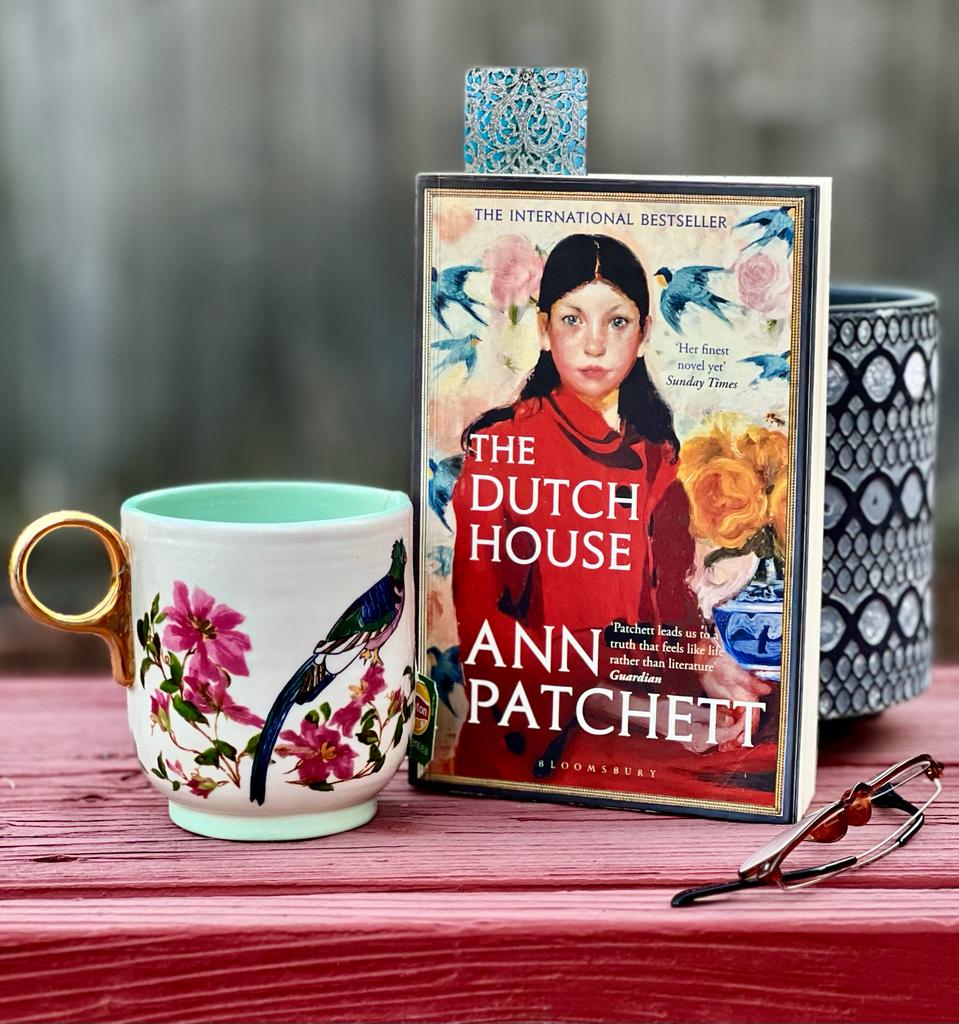

THE DUTCH HOUSE by Ann Patchett: A REVIEW

Everyone’s been raving about Ann Patchett and her fabulous books. A few years ago I had heard of her Bel Canto, how well-received it was, making waves in literary circles, and I had marked the book down for a later read. But then I recently picked her The Dutch House instead, trusting my instincts of trusting an old school-friend’s recommendation! The avid and discerning reader that she is, I often blindly follow her suggestions. And I was amply rewarded. What a page turner!…

-

O YE, OF LITTLE FAITH

I was born and raised a Hindu, embedded with a moral compass that drew largely from the Hindu religious tradition, given its pointers to the good and wholesome way to live my life, the virtues to imbibe and vices to eschew. I grew up among friends and neighbours, a mix of many religions among them:…

-

WHAT DO WOMEN DO, ANYWAY?

What I like about TV and web series is that they come with the luxury of time and space, allowing the arc of the story to develop in enough detail. Events unfold at their own pace, and personalities reveal their inner complexities, measure by interesting measure. That additional time and space also allow the viewer…

-

LATA, MY DEAR…

It’s a summer evening, my parents are out in the garden. She in her cotton saree, juhi buds wreathed into a gajra in her hair. He in his kurta pyjama, his thick black spectacles wedged firmly on his nose, his gin and lime idling in his hand. Music playing, always heavenly heady music. Maybe, a…

-

QUIET PLEASE!

Discourse is becoming increasingly fractious, I find. Frivolously fractious too. So much so that labelling it as discourse is an insult to the word. There are more verbal brawls today than there are respectful discussions. Am I growing out of date, I ask myself, when I fear I cannot keep pace with the histrionics that…

-

A PLACE CALLED HOME

Returning home has always been an absolute joy for me. Howsoever fascinating and fruitful the sojourn abroad, the promise of retrieving my own customary space to reclaim myself, my own bed to dream in, my own land and sun and soil, happily lures me back every time. I remember one morning on reaching home from…

-

LEAD THE KIND INTO THE LIGHT

Kindness attracts me immensely. There is a quiet luminescent glow to it in comparison to which the brightness of wit and the radiance of genius pale. Of course, I admire men and women of intelligence. We, of the human race, benefit from their curiosity and their inventiveness, the questions they ask and answer, pushing the…

-

The Sun That Sang

—

It was in the middle of the afternoon on a regular weekday. I was driving to school to pick up our daughter. Well, the car practically drove itself for I was hardly conscious of steering it. It was on its customary route, taking the usual turns this way and that with indicators flashing accordingly, stopping…

-

Coping. Rebooting.

It hasn’t been easy, has it? This year and more of struggling, surviving, losing, coping, adjusting, wrapping our heads and hearts, minds and bodies around the new emerging normal. All yet fluid and floating, unsettled and undefined, allowing this today, prohibiting that tomorrow, and then perversely changing everything all over again. At first life threatened…