Ever since I started writing I have been questioned off and on about my choice of language, English. There are those among my circles of family, friends and acquaintances who are puzzled as to why a person born and raised in a Maharashtrian family, who has been living in Pune for the past several decades, and who is reasonably capable of articulating her thoughts in Marathi should opt for English when formalising them in print.

I try when I feel patient enough, which is rare, to explain the linguistic particulars of me and myself. I grew up in Jamshedpur where my father worked for Tisco, now known as Tata Steel. I went to school there with my older sisters and many other children from families that hailed from different parts of the country. All working in a town far away from their native origins, all building a cosmopolitan community or a prototype of an integrated nation, all happily melding their respective ethnicities in one melting pot. Our mothers would speak in different native tongues at home and all of us young children searched for the one bridge that could effectively and happily connect us all. Our parents opting to send us to a school that taught in English, that bridge was forged and we were joined.

So that was that. English came home and stayed. But not as a guest. Rather, as one of our own. On par with our own maternal languages. My mother befriended languages as we do people and soon she too was reading Shaw and Cronin and Maugham and Christie and Wodehouse just as we were, and as easily as she still read her Marathi litterateurs and the Sanskrit verses of her favourite Kalidas. While we were and still are fluent in Marathi, Hindi and English, the last soon became our default medium of discourse, of all debates and discussions. At home and outside it.

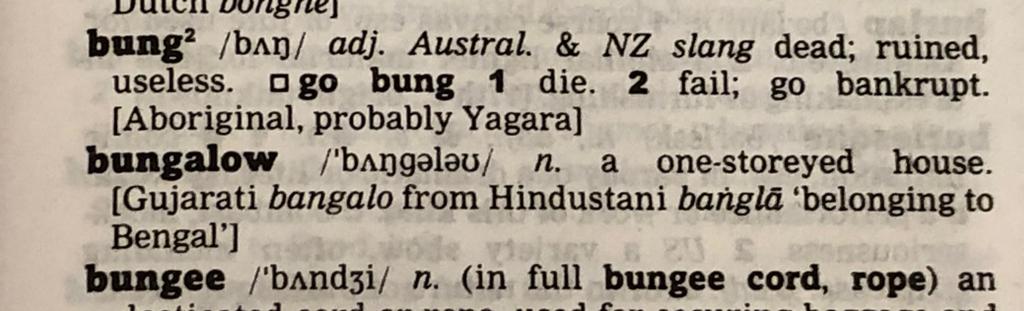

English still is my language of thought and action and emotion. And thence of writing. Of course, I’ve borrowed words that belong to our own soil and have blossomed under our own sun. I still adhere to calling our ubiquitous aromatic kadhi limba or kari patta by their Marathi or Hindi names, rarely referring to them as curry leaves, and most certainly not when I’m actually tossing them in hot oil. Or, jhootha/ushta is just that and I know no English equivalent that expresses its exact or entire intent. Just as chit, loot, pyjama, bangle, bungalow, veranda and so on were incorporated by the British into their dictionaries, I’ve added my own selection of Hindi and Marathi words and catch phrases to my everyday parlance in English. My own version of fusion.

But I look around me and I find a peculiar paradox.

On the one hand, I see an increasing embracement of English as one of the necessary tools in today’s economically imperative globalisation. With the ongoing technological revolution and its windfall of information access on devices that can fit into our palms, it wouldn’t be entirely inappropriate to say that we hold the world in our hands. But that world doesn’t necessarily speak nor understand the languages we grew at home. The ones we call our mother tongues. Out there we have Chinese (Mandarin, as its most popular variant), Spanish, Arabic, German, French, Russian and Japanese. And, of course, English, with which we are already familiar and have heard spoken in our midst since the past couple of centuries and more. From which words like officer (afsar), hospital (aspatal), captain (kaptaan), bottle (botal) and so on had already been lifted, modified and made our own. And from which today words like enter, search, like, copy, paste, send, share and such similar virtual commands have swiftly slid and seeped into our native tongues and are used indiscriminately even by those who have never stepped into a school and would hardly appreciate the foreign origins of parts of their everyday lexicon.

On the other hand, I also come across a bristling resentment against the very same language. It is seen as an obdurately surviving relic of our unhappy colonial past. A need to refute a language that was once taught to the ruled subjects to produce men that could effectively serve their royal British Majesties. A vestigial emblem that reminds us of of our political enslavement and economic plunder. That we should choose to express ourselves in that language could, according to resurgent nationalists, only indicate an abject but resilient colonised mind-set, a reluctance to right past wrongs, and an apathy in restoring pride and prestige to what was and is home grown. Moreover, they remind us, English was and is essentially elitist, a dividing tool, the separator of the socio-economically and politically powerful classes with high prestige quotients from the masses who are more comfortable expressing themselves in their own respective vernaculars. The still entrenched divider between the rulers and the ruled, perpetuating cruel condescension. A passport to vacuous snobbery. Shame! Times have changed, they remind us. Be Indian. Speak Indian.

But I have never regarded English as un-Indian. On the contrary, it is to me my means of communicating with my Gujarati, Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu, Kashmiri, Bengali, Bihari, Odiya, Malayali friends. All kaleidoscopically Indian. To easily understand and be understood. To share. To bond. To commit. My national integrator. Very early on I could guess who was a Tamilian, who a Bengali, or a Gujarati, or a Punjabi, just by hearing their unique accents, their elongation of certain vowels, their suppression of certain consonants, their distinguishing phonetics, diction, typical mix-ups in syntax, their own respective native tongues stamping their identities with authority on the adopted one. But that just added bags and bags of fabulous flavour. And helped us appropriate what was once foreign as one of our own. Indian English.

And what exactly and uniquely is it to speak indigenous Indian? Tamil? Bangla? Dogri? Marathi? Which variant of Marathi, the one spoken in Mumbai or Nagpur or Kolhapur? Or the one that Pune superciliously believes to be its sole chaste avatar? Our much touted diversity could actually become a stumbling, if not dividing block, if we chose to revert exclusively to the homespun. Hindi, that was once adopted as our national lingua franca has really not made the inroads expected. There are those that disdainfully look down upon it or plainly refuse to speak it, much like the French refuse to speak English, fearing that giving way to the language of the northern plains may swamp their own particular ethnicities. Linguistic roots are a matter of ethnic pride and nobody can or should be expected to surrender that. And the longstanding power tussle that festers beneath the stitched bonhomie of states comes up front and close, because yielding precedence of one’s language to another’s is as susceptible to tensions as relinquishing water from rivers. The lingual divides flare up and subside intermittently, either spontaneously or deliberately, depending on who is looking to catch the eye and ear of the public and therefore looking for an inflammatory grouse to vent.

Then, what to do? How does this paradox get resolved? I can switch easily between Marathi and Hindi and English. But can we all? And is that even enough? How do I gain access to the ideas that could enrich my life but have been expressed in languages beyond the reach of my comprehension? Much is lost in translation, I agree, but that remains my only realistic hope of understanding what, for example, the farmer in that remote corner of the northeast thinks about the rest of his country and countrymen. On the other hand, the local municipal school’s watchman’s daughter who aspires to be a computer scientist was stumped by the standard of English in her text books. Why have not our books been written in my language, she asks in frustration. Really, why haven’t they? Or, for example, why hasn’t that Bible of medicine, Gray’s Anatomy, been translated into all our regional languages yet? Why should a girl who has studied in Marathi all her schooling life suddenly be expected to improve her English skills just so she can pursue her specialised academic interest? But the committed and motivated girl that she is, she buckles down and does, confidently melding her learned English medical jargon with her instinctive Marathi when giving instructions to the nurse assisting her in getting our babies born. Like that only.

And so this conundrum of languages continues and we trundle along speaking bits of this and bits of that. And get by. Make do. Our language jugaad. I chat with my neighbours in Marathi, sing in Hindi and write in English. And when I tell the weaver in distant Kanchipuram who has been modestly making ends meet while always gloriously making Indian that I want a beige coloured saree with a dull gold temple border, I know that, for all our proud espousal of our linguistic roots, he and the traders representing him are familiar with all the key English words. So I don’t need to learn Tamil, nor he Marathi. It’s business, baba! Just click on picture, press like and send. Simple.

Leave a Reply